Stories and recollections

Discovering my voice

I consider myself extraordinarily fortunate to have been born with a voice that enabled me to become a professional singer. As in every career, there are ups and downs, it is most certainly not all glamourous and the stresses of performing professionally year in year out are real and considerable. But the opportunities and experiences my voice made possible I could not have dreamed of as child growing up in Stirling, Scotland. The joy of performing exceptional music with such talented colleagues and artists across the world for the best part of three decades is something I will forever treasure.

My family was not particularly musical, although my father loved to play the piano, had a very good ear and a good singing voice. Growing up I realised from a fairly young age I could do something my friends could not. It is difficult to convey the feeling I has as a young child in words, but it was as though my voice was my special secret – something I carried around with me that I knew other people didn’t have and which gave me confidence.

Thinking back, it probably wasn’t quite as secret as I imagined it to be, because I do recall often being asked to stand up and sing in class when I was still at primary school. My brothers (the younger of whom was slightly scarred by the fact he was also asked to stand up in class and sing because, surely, he must be like his sister) like to joke the first memory they have as young children was me singing a top C. And my father initially had hopes that I might be a pop star until he realised my voice was better suited to Mozart than Dusty Springfield!

But I wouldn’t say I seriously contemplated life as a musician until I was about to go to University. I might have flirted with it from time to time – one memory is going to hear Margaret Price sing at the Albert Hall in Stirling and feeling a strong conviction that I would like to do that. As I was a relatively shy child, such moments of certainty were not the norm. But it was only when I had gained a place to study languages at St Andrews University that some people who had noted my vocal talent started to question whether this was the step I should be taking. Specifically, I must credit George Mc Vicar, then Director of Music in Stirling, who took me aside and said that in his opinion I should be using my talent and applying to the Royal Scottish Academy of Music and Drama (the RSAMD) as it was known then. I loved singing, so I embraced his advice and encouragement enthusiastically. The audition went well, and I was offered a place, although with the advice that as I already had gained entrance for university perhaps I should do that first and then come to the Academy. Instinctively I knew I would go immediately to the college – and that is what I did, a decision I have never regretted although many years later I received with great pride and pleasure an honorary doctorate from St Andrews University

It was in my second year at the Academy that I met Ena Mitchell. The teacher I had been studying with in my first year became ill and left his post as head of singing. At the same time, the then Principal of the college, Henry Havergall, wanted me to sing J.S. Bach’s cantata Jauchzet Gott in allen Landen at an Academy concert. He asked Ena, who was teaching at the Academy, to coach me for the work. From that very first introduction, I knew I had met someone whose language I understood completely. We just clicked. She made a huge impression on me with her personality, her musicality and her extraordinary gift for teaching and sharing her knowledge. I was a very young singer with a natural instrument and she taught me to make the most of it. I remember her saying there is no use having a Steinway if you don’t know how to play it. I was lucky enough to have a natural instrument and she taught me to play it – and in a way that made sense to me, that I could understand and to which I could respond. We did plenty of exercises, but fundamentally she taught technique through the music. I loved the way she would take the song apart technically and put it back together. She had the ability to put her finger on whatever problem occurred, know why it happened and what to do to rectify it. After that kind of forensic examination, you knew you could really sing that piece! She was a superb musician, a wonder and an inspiration, who taught me everything I know – every aspect of the art of singing. I owe her everything and her picture still has pride of place on the piano in my music room.

Dundee, 1971

“Margaret Marshall, from Stirling, an engaging young soprano, who recently won a Caird Trust music scholarship to study abroad, was soloist. In the Mozart concert aria “Ch’io mi scordi di te” she allied her warm, expressive voice to firm technical control in the long phrases, and her tone was beautifully Mozartian.”

Bach, St John Passion, Kurt Redel, Le Monde, 18 April 1976

“The vigorous, completely radiant voice of Margaret Marshall.

Performing in Lourdes.

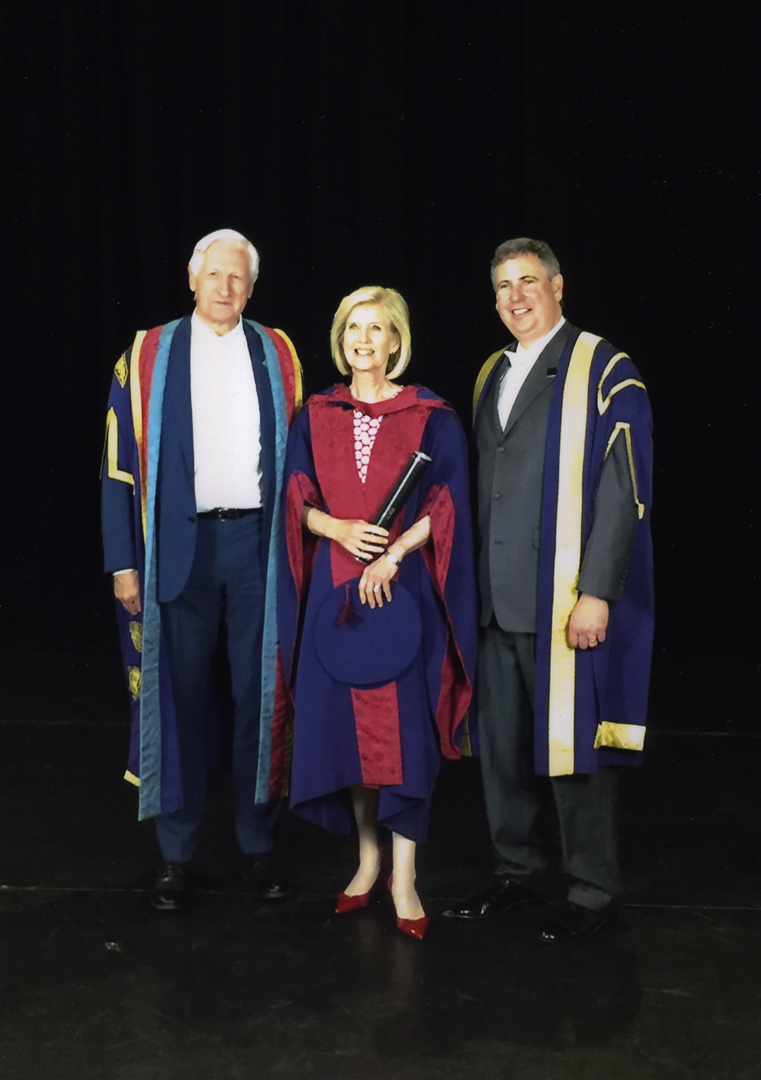

Receiving an honorary doctorate from my old music college from Principal Jeffrey Sharkey and Chairman Nick Kuenssberg.

My international breakthrough with Purcell and Bach

The first piece in the “Songbird” programme, is Purcell’s The Blessed Virgin’s Expostulation. This recording is from the finalists’ concert following the 1974 ARD International Vocal Competition, where I won first prize. As it happens, at the time I was seven months pregnant with my first child. I recall my singing teacher in Munich, Hans Hotter – who had suggested entering the competition well before I knew I was pregnant – being pleasantly surprised that I returned to take part. It didn’t really occur to me not to – after all I was not unwell, only pregnant! I would consider that quite normal – my daughters think it indicative of my allegedly single-minded and determined nature! Either way, back to Munich I went. Winning wasn’t on my mind, I just wanted to sing my best – before going back to Scotland and having my baby. And I do recall I rather enjoyed singing when pregnant as it felt as though there was an extra level of support.

At that time in my career I hadn’t yet performed any complete operas apart from at college, so my chosen repertoire comprised oratorio and lieder. I remember hearing these enormous voices singing opera from the concert hall. Listening too much could have had a negative impact, so I consciously never went to hear any of the other singers perform in the various rounds to avoid being distracted by what they were doing. Having come through the three piano-accompanied qualifying rounds, I found myself in the final round with the orchestra. The Jury had initially wanted me to sing “The sun goeth down” from Elgar’s “The Kingdom,” but at the last minute they couldn’t get hold of the orchestral parts so asked me instead to sing the Purcell along with the first movement of J.S. Bach’s cantata “Jauchzet Gott in allen Landen.” The Purcell is usually performed with a piano or harpsichord – and is not so well known in its orchestral version. The work showcases Purcell’s genius for setting words and capturing changing emotions. It is an extremely dramatic work – from the coloratura in “Cruel Herod’s way”, to the pathos when Mary questions why her child has disappeared, through to her desperation when she calls for Gabriel and the realisation that he won’t come back, leading to her desolation in “flattering hopes.” Along with Jauchzet Gott, it certainly gave me plenty of opportunity to showcase my best vocal talents. Jauchzet Gott is a wonderful exulting coloratura aria which I loved to sing. I first performed it at the RSAMD – indeed it was when I first met Ena Mitchell – and also performed it at the last concert I gave before my retirement. Every singer is unique in what they find more, or less, challenging to sing. I was fortunate in that I seemed to have a naturally agile voice and so really enjoyed singing works like this.

The winner was announced in German. I had to ask the person next to me if they could confirm who had won as I wanted to make sure I had properly understood what had been announced. Of course, when it became clear they really had announced my name – in fact they awarded the first prize to “Miss Marshall mit baby” – I was absolutely thrilled and elated.

The world of opera and classical singing is highly competitive and winning this competition was huge in terms of the opportunities it presented. Now I had proof of achievement, finding an agent was not the challenge it had been before. I signed with Harold Holt as it was then known. But the most rewarding part of the prize was that it included invitations from various German radio orchestras, who had supported the competition, to give concerts and do studio recordings. These recordings were then broadcast throughout Europe giving me a huge platform on which to perform. Some of these recordings feature in this programme.

But first of course I had to have the baby!

Shortly after winning the competition in Munich, when I was seven months pregnant with my first daughter.

Bach, Easter Oratorio, Kurt Redel, Le Monde, 20 April 1976

“Margaret Marshall, soprano, is one of the finest discoveries of recent years. A perfect technique carries this radiant voice, more varied in colour than some of her world-famous colleagues, full of life and energy, of exquisite expression where the vocalisation pours forth inner enchantment and surpasses technical virtuosity.”

After Munich – opening doors, embracing baroque and first recordings

Winning first prize in the Munich competition opened many exciting doors for me. One of those doors was the invitations to sing with German radio orchestras. Germany has an extensive network of first-class radio orchestras and one of the great benefits of these engagements is that the concerts were broadcast live on German radio.

One of my first engagements (after I had given birth to my first daughter Nicola of course!) was to perform sacred music with the Collegium Musicum for the Cologne Radio. I recall the visit very clearly as we stayed in a nunnery which was quite a different experience but one I remember finding very tranquil and relaxing.

The programme included Baldassare Galuppi’s Rapida Cerva. Most people have probably never heard of Galuppi. I hadn’t at the time but soon found out he was a baroque composer born in 1706 on the Venetian island of Burano. He had been very well appreciated during his lifetime, but following Napoleon’s invasion of Venice in 1797, much of his music was scattered around Western Europe and in many cases either destroyed or lost. Such was nearly the fate of the Rapida Cerva, but fortunately it made its way into the Santini collection where it was discovered in Munster by a man named Dr. Rudolf Ewerhart.

Rudolf was a fine conductor and organist who had himself edited the piece for soprano, organ and string orchestra. I believe this was the first time it had been performed for centuries! Rudolf and I hit it off from the start and the music was very well suited to my voice. Shortly after the concert, I received an invitation from Rudolf to make a commercial recording of the work, along with Johann Christian Bach’s Salve Regina – this time with Die Deutchen Barocksolisten.

It was an exciting invitation on multiple levels. It would be my first recording. And furthermore, it was the first time ever the Galuppi would be recorded and, I believe, also the first recording of the Salve Regina, an equally delightful piece of music to perform.

It was a very intense experience. We recorded both works over two days with a concert of both pieces thrown in for good measure at the end of the second day! Take it from me that is very hard work and the next recording I did was a very different experience! But I was thrilled with the result, which you can listen to via the YouTube links. Rudolf and I enjoyed many subsequent collaborations together and remain in touch to this day.

Conrad Wilson, The Scotsman

“Having won the 1974 Munich International Competition, the Stirling-born soprano looks like having an exciting career ahead. Her prentice years of performing oratorios in draughty Scottish churches have paid off. Now she sings Gluck’s “Orfeo in Florence and is pursued by the record companies.”

For the love of Vivaldi!

I recorded a lot of Vivaldi between 1975 and 1980. My elder daughter says one of her first memories is of me singing Vivaldi. Which is certainly possible as she was born in 1974 and there would have been a lot of Vivaldi going on in our house in the following years.

Much of that was the complete recording of Vivaldi sacred music – which is a lot of music – but also the opera Tito Manlio. It was all conducted by Vittorio Negri, who was a great champion of Vivaldi and had persuaded Philips Records to invest in these recordings. Vittorio was an extremely talented man – not just a wonderful conductor but also a very talented producer – something I had not realised until we met subsequently when he was the producer of a recording I made of the B Minor Mass, conducted by Sir Neville Marriner.

It was a joy to work with him, particularly as a young singer. Vivaldi can sound quite deceptive – it looks very easy on the page but holds many surprises especially in some of his coloratura passages which can be quite difficult to navigate. But I have always loved singing coloratura and so embraced the opportunities that Vivaldi gave the soprano voice.

It was also the first time I met Jeffrey Tate, who was the harpsichordist for the recordings and also a talented and successful conductor. I remember Jeffrey flinging off some suggestions for ornaments at a rehearsal which were so brilliant I carefully notated them down. The next day when I added them in during the recording, he asked me where the ornaments came from as he liked them so much – he had added them in so naturally he didn’t realise they were his!

There was a seemingly never-ending amount of music which required seven CDs to capture in its entirety (available on Spotify: search Vivaldi Sacred Choral Music, Vittorio Negri). I feel privileged that I had the opportunity to record this wonderful music as part of a complete series, along with some extremely talented musicians including my dear friend Ann Murray whom I first met on this recording.

With so much wonderful music to choose from, it was difficult to pick out a few pieces to include in this programme. I narrowed it down to four pieces. The “Canta In Prato” from the Introduction to Dixit Dominus. And “De Torrente” from Dixit Dominus. Two from Tito Manlio – “A la caccia” and “Non ti lusinghe la crudeltade”. (NB I am waiting for A la caccia to be uploaded to Spotify by Decca who have kindly agreed to make it available. In the meantime, I have included the link to “Combatta un gentil cor”).

The Introduction to Dixit Dominus is simply an exhilarating piece to sing with exuberant, repeated staccato colouring the joy of the notes. My daughter Nicola, who has been instrumental in putting this website together, asked me how you sing staccato as she imagines it to be very difficult. I told her, rather unhelpfully I suspect, that her question was like asking a violinist how he plays pizzicato. I don’t mean to make light of it, but an excellent skill or performance is not something you achieve overnight – ultimately everything in singing is down to support, technique, knowledge and experience – which takes years to accumulate.

The “De Torrente” is its opposite in mood and always reminds me of Venice and the flowing water. It is a beautiful calm melody, an exquisite piece of music and just as challenging sing in its own unique way, demanding an exquisitely sustained line throughout.

The sacred music was all recorded in London and I recall it being an extremely enjoyable period. Tito Manlio by contrast was recorded in East Berlin in 1977. It was my first time there and a big adventure at that time, even more so as I was six months pregnant with my second daughter. I still recall vividly being struck by the contrast compared with how we lived and remember how the musicians of the East Berlin Chamber Orchestra were so pleased to see us, delighted we had come to perform with them and so grateful to receive any books or magazines that we could give them. The recording always took place in the evening so there would be complete silence uninterrupted by the noise of traffic, although I can remember a take being stopped to allow an airplane to fly overhead.

Tito Manlio has since become popular with star singers for its virtuoso arias – but this was the first time the work had ever been professionally and commercially recorded. This was thanks to Vittorio and his passion for Vivaldi. My part Lucio – which I also sang on stage at La Piccola Scala in a leather tunic and boots, my first and only trouser role on stage – had some of the most beautiful and show-stopping arias for soprano. “Combatta” with trumpet, and “Fra le procelle” and “Alla caccia” with horns which makes the colour of the aria so exciting. These early experiences during my career mean that Vivaldi will always be one of my favourite composers to sing……so much wonderful music…..but then there is J.S. Bach and Mozart.

Taken in East Berlin, when recording Tito Manlio with Vittorio Negri.

Singing Cosi fan Tutte with my friend Ann Murray, who I first met recording Vivaldi in the 1970s.

Vivaldi, Sacred choral music.

“Margaret Marshall must be the equal of that soprano of the Pieta who was so lavishly complimented by all visitors to the conservatory,”

Vivaldi, Sacred choral music

“The lion’s share of the solo work is admirably done by Margaret Marshall. From the first entrance in the Introduzione al Dixit….her work is stunning. She even manages to get in some breath-taking divisions in the da capos. Ann Murray is her equal in the duet Virgam virtutis tuae” from the Dixit Dominus. The ease in which they toss the passage work back and forth between them is thrilling.”

The two geniuses – Bach and Mozart

Bach and Mozart. My two favourite composers. If I were pushed to name only one I would not want to – and indeed could not – choose between these two geniuses.

Sitting across the baroque and classical eras these two prolific composers straddled an outstandingly productive and evolutionary period for classical music. They are a revelation – both for listeners and singers.

The recordings of this Bach cantata and the Mozart concert aria “Ah lo Previdi” are with the Saarlandischer Rundfunk Orchester, the Bach conducted by Hans Zender and the Mozart by Hanns-Martin Schneidt. After winning the competition in Munich, Dr. Christoph Bitter, the Intendant of the Rundfunk, invited me to sing Haydn’s “Die Schoepfung.” I was then invited back for a series of concerts which featured these works.

Bach and Mozart may be equally great composers but that does not mean you approach them in the same way. For example, when singing a Bach aria, accompanied by a trumpet, oboe or flute, I tried to match the sound of the instrument that was accompanying me. I also tried through the phrasing to find the style of the composer first, and then highlight the important words. All this and more, I learned from Ena Mitchell, my teacher, who was extremely talented at capturing just the right style for each composer and imparting how to capture this in a precise and understandable way.

Bach is very instrumental, with clean lines and a purity of voice. In Bach, for me, the voice is truly an instrument. The vocal line could be played by an instrument and so the voice must sound that way. Think of the wonderful aria “Aus liebe” from the Matthew Passion. In this cantata, “Non sa che sia dolore” there is also a wonderful duet between the flute and the voice – and I was delighted to be reunited for this performance with the flautist Roswitha Staege whom I had met in Munich. I hope, when you listen to it, you hear not simply a voice and a flute – but two compatible and complementary instruments combining their own individual sound to make sublime music – that is the brilliance of J.S. Bach.

In Mozart arias you are not going to try to sound like an instrument in the same way. In his sacred work it can be different – think of “Et incarnatus est” from the C minor mass where you can intertwine the voice with the flute. But on the operatic stage it is generally different. You must think about the drama of the piece in a different way.

With Mozart you also look at the story and the libretto. I love the way he always gives you a clue before you come in with a recitative, setting the scene musically before the singer starts. You still have to sing the lines, you still have to sing beautifully, you still have to think of the words, you still have to think of the drama of the piece – but you do that in the style of Mozart.

When I performed the “Ah lo previdi,” along with other Mozart arias, I was yet to sing a full opera on stage as a professional singer. It was the first time I had performed the piece, which is a big, dramatic scena. The conductor supported me perfectly – taking breaths with the orchestra when I took breaths and enabling a seamless and beautiful binding between the voice and accompaniment. I love the drama of the work, which has so many different mood changes from the first accompanied recitative to the beautiful last aria, “deh non tardar.” It is almost a little opera in itself.

Following the concert Dr Bitter invited me to sing Donna Anna on the stage in a production in Frankfurt. Ena advised that I was not yet ready and should decline the opportunity, which I did. It is difficult as a young singer to turn down such invitations, but I trusted Ena implicitly and for a young singer it is critical to build in the right way at the right time. Fortunately, Dr Bitter understood and stuck with me. At the same time, it was wonderful to be able to explore Mozart arias, including “Non mi dir”, in a concert setting. And opera would come – at the right time, in the right way, and with a most brilliant conductor.

I always loved singing Mozart, and Arminda in La Finta Giardiniera was a lot of fun. This is from a performance with Frankfurt Opera.

Mozart, Exultate Jubilate, with Sir Alexander Gibson

“But the conductor, undeniably, was Scottish – and so was the young soprano, Margaret Marshall, whose account of Mozart’s Exultate Jubilate, was remarkable for its beauty and poise, with the daunting semiquaver runs in the final “Alleluja” scrupulously phrased and articulated.”

Opera is wonderful, but my heart belongs to oratorio

Part 1

I always loved singing oratorio. To me the genre is absolutely the equal of opera and indeed if I were pushed to choose a favourite work to perform, it would most likely be an oratorio. That is a very personal choice and others would choose differently. But the composers I loved to sing – Bach, Handel, Mozart, Purcell, Mendelssohn, Brahms, Britten and Vaughan Williams – were all the authors of exquisite works for the voice outwith the medium of opera.

There is no one path for a singer to tread, and our individual journeys are all unique. As my career progressed, I spent an increasing amount of time singing opera, but my heart always reserved a special place for oratorio. Indeed, I have never liked the categorisation of classical singers as “opera singers” because that gives a hierarchy to opera that I feel is unfair to other classical musical genres. That is not to minimize the demands that singing an opera puts on singers – three plus hours out there on the stage with all the pressures on your voice to perform perfectly are incredibly demanding – and only become more so, not less, over time. I believe that the skill required for other genres of classical singing – namely oratorio and lieder, should be celebrated in the same way.

I remember Hans Hotter telling me that oratorio would help my opera, and lieder would help my oratorio – and how right he was. The three different genres enrich each other and only by appreciating the differences can one come close to mastering the intricacies of any. Opera on the surface may be the most dramatic of the three, but intimate lyrical lines have their place in opera as much as they do in lieder. In the concert hall there might be an opportunity for nuanced singing as there is in a typical lieder venue. And oratorio can be the dramatic equal of anything you will find on the operatic stage – just think of Elijah, the wonderful soprano aria Hear ye Israel and the widow woman’s duet.

A lieder recital. Opera, oratorio and lieder enrich each other.

Elgar, The Light of Life, Royal Liverpool Philharmonic, Sir Charles Groves

“In radiance of tone, clarity of enunciation and her ability to position both in the space of the Albert Hall, Miss Marshall proved her place in the first league of oratorio sopranos.”

Mendelssohn, Elijah,

“Margaret Marshall was the soprano, powerful and pure.”

Mozart, Requiem, Berlin Philharmonic, Carlo Maria Giulini

“Miss Marshall acquitted herself with great distinction. With her burgeoning operatic career, including a string of performances in coming weeks as the Countess and Fiordiligi in Cologne’s Mozart cycle, it is easy to forget that until a few years ago her career was confined almost entirely to the concert platform. That discipline has always stood her in good stead, as her Berlin performance illustrated. She was the only member of the quartet of soloists to demonstrate the technical ease, purity of tone and certainty of pitch that the music requires.

Singing Fiordiligi in Michael Hampe’s acclaimed production for the Salzburg Festival, conducted by Riccardo Muti.

Opera is wonderful, but my heart belongs to oratorio

Part 2

My beliefs are of course very much shaped by my own experience. I performed my first opera – Gustav Holst’s Savitri (in the role of Savitri) – while in my first year at the Royal Scottish Academy of Music and Drama in 1968. It was reviewed very favourably I remember in the Glasgow Herald, but from my perspective as a 19-year-old student it was not a confidence inspiring experience. I distinctly recall being taken to task by the director of studies who seemed to take pleasure in telling me that I may be able to sing, but I couldn’t act. It was one comment, but it was not a helpful one. I had been admitted to the college because of my vocal talent, not my acting skills. He had no helpful contribution to make as to how I could improve my acting but led me to believe I was somehow lacking in my ability to perform. Thank goodness for Ena – she worked with me on the production and gave me the confidence to do the performances. The reviews were very positive, but the memory did not fade quickly, and it was why I felt quite comfortable sticking to concert repertoire for the best part of the next ten years, including the first three years of my professional career post Munich.

I was invited to sing quite soon after the Munich competition – Capriccio by Richard Strauss with Glyndebourne Touring Opera and Donna Anna in Don Giovanni with Frankfurt Opera, but Ena said no. It was not that I could not sing the music of these roles, but that Ena quite rightly felt that the overall undertaking was too much at that time of my vocal development. Looking back, I feel privileged that I was able to turn down such opportunities – because I had a teacher whose advice and judgement I trusted so completely, and was fortunate to have many other exciting invitations to accept.

Orfeo ed Euridice, John Eliot Gardiner, 1976

“Messana’s eloquent, exquisite phrasing was matched by Margaret Marshall’s Eurydice. Miss Marshall’s talent has been noted in other areas; here it blossomed into truly operatic conviction – surely an Elvira and Electra (Mozart’s) in the making.”

Mozart, Cosi fan Tutte, Salzburg Festival, Vienna Philharmonic, Riccardo Muti

“Miss Marshall has gained in poise and dramatic conviction through her Salzburg experience. Come scoglio and Per Pieta were such pinnacles of vocal grace, beauty and technique, that she can have few peers among Mozart sopranos today.”

Opera is wonderful, but my heart belongs to oratorio

Part 3

Some of these opportunities are captured in this programme – including the glorious aria “Guardian Angels” from the Triumph of Truth and Time by Handel. Along with Bach, Handel is the undisputed King of the Baroque era. Yet his music is quite different to Bach’s – both to listen to and to sing. As a singer this is about understanding the style of each and adapting accordingly how you approach the vocal line. Both wrote exquisite music for the voice but Bach, I believe anyway, treats the vocal line in a more instrumental and angular way that demands a flawless sound, but still one imbued with deep feeling. The challenge is to capture that feeling and sound in your voice so that it integrates perfectly with whatever instrument it is partnered with.

In Handel there is more freedom, more ability to differentiate the voice from the orchestral accompaniment. Both are equally rewarding to sing.

The Triumph of Truth and Time is a very interesting work in that Handel wrote three iterations of it over his lifetime. The first version, “Il Trionfo del Tempo e Disinganno” was written when he visited Rome in 1707 at the age of 22. Subsequently he returned to the work twice, the first time resulting in “Trionfo della Verita” and the final time “The Triumph of Truth and Time” written in 1737 30 years after his first look at the work.

The performance of this aria is from the Handel Festival in Gottingen, with the conductor Gunther Weissenborn. We performed two versions of the work – the original 1707 version and the final 1737 version in two concerts over three days. I do have a recollection of preferring the Italian version, which was full of magnificent arias, bubbling with the youth of the exuberant Handel, but there can be no denying this is an exquisite melody and I am delighted to have this recording. In the aria, my character Beauty, after looking in the mirror of truth, announces her intentions to pass her days in sacred solitude and invokes her guardian angels to direct her. I do remember being slightly shocked when this vast score arrived, with my part written in the soprano clef. Fortunately, I had some good friends to call on who helped me write it all out in the treble clef and stick it into the score making it even heavier to carry around. This memory reminds me of when I saw an unusually thin score of Rosenkavalier. I remember asking the owner, who sang the Marschallin, why her score was so thin. “My dear,” she replied, “why should I carry other people’s music around with me?” She had simply cut out the large parts of the opera where her character did not appear. Definitely better for your back but not something I ever did!

Singing alongside me in the Handel performances were some great British singers, including Helen Watts and Norma Proctor. They were both very supportive and kind to me as a young singer – and indeed Helen became a dear friend – but they were also the font of very practical and useful advice. German towns, indeed many continental towns but I didn’t know it then, have clocks that chime loudly on the hour. I remember coming down to breakfast on the day of the first performance having slept badly due to the noisy chiming, and relaying this to Helen, who cheerfully told me that she had slept like a baby and that I needed to invest in some Ohropax ear plugs. After that I never travelled without them – you just never know when there is going to be an hourly chiming of a clock the night before a performance!

Handel, Samson

“The evening belonged to Margaret Marshall. What a wonderful and memorable duet “Let the Bright Seraphim” between soprano and trumpet. What an appealing solo “My Faith and Truth” was. From Margaret Marshall’s appearance with the magnificent “Ye Men of Gaza” all were enthralled by her every intonation”

“Margaret Marshall proved in many ways the single most memorable element in the whole performance. Even more than in the opera house, Miss Marshall provided purity and poise, an unfailing flow of golden tone perfect diction and immaculately precise divisions.”

With Catherine Gayer after a performance of Handel’s The Triumph of Time and Truth.

The Act 2 finale of Mozart’s Cosi fan Tutte from the Salzburg Festival, conducted by Riccardo Muti.

Opera is wonderful, but my heart belongs to oratorio

Part 4

My love for oratorio continued throughout my career. I love the combination of music, drama, beauty and wit. I have to say I also preferred having the orchestra behind me, literally supporting me as I performed compared with an opera house when the orchestra is in the pit, creating a feeling of separation. I have mentioned this to other singers and it was clear they did not feel the same so this was very much my own experience but I preferred to feel that proximity with the orchestra as we performed together.

But after my first tentative introduction to opera with Savitri as a student, I was extraordinarily fortunate with my first professional opera engagements. In 1976, I was 27, and my agent organised for me to do a studio test at EMI on Abbey Road. I chose some Mozart and Strauss to sing and John, who of course subsequently became a very highly regarded and successful producer with EMI, was accompanying me. When I arrived, they told me that there was a young Italian conductor in the studio who was coming in to listen. It was Riccardo Muti. He is nine years older than me, so would have been around 36 and clearly already an enormous talent, but fortunately I was not fully aware of that. I remember thinking he didn’t look as though I was making much of an impression on him, but as the session continued he started to engage more and after a short while told John he wasn’t needed any more and sat down at the piano himself so we could work together directly.

I don’t think he was too impressed with my Italian but fortunately he did like my singing. Not long after he invited me to sing the role of Euridice in Gluck’s Orfeo ed Euridice in Florence. This was a role I had already performed in concert so fortunately this time Ena said yes and off I went. I still remember being nervous about the prospect of having to act a character on stage after the Savitri experience and so Ena arranged for me to see an acting coach from the Manchester College where she was then based. This lady took me to the British Museum to study the ancient Greeks and their flowing robes in anticipation of the fact that would be my costume. Hilariously when I got to Florence there were no flowing robes but I’m sure nevertheless it was a worthwhile experience. I recall the production with great affection – I was very lucky in that the Orfeo, Julia Hamari, was very generous and supportive towards me, so much so that I named my second daughter Julia after her.

Maestro Muti invited me back to Florence for Le Nozze di Figaro – and my operatic career began in the way that was right for me and my voice, with the support of someone who is now regarded one of the most talented conductors of our time. I consider myself extremely fortunate to have had the chance to collaborate with him.

Gluck, Orfeo ed Euridice, Teatro Comunale di Firenze, Riccardo Muti,

Opera magazine, July 1977

“The revelation was Margaret Marshall (Eurydice): this young Scottish lyric soprano, in her first stage role, used her flexible, warm voice with the phrasing, musicianship and variety of colour worthy of a singer of twice her experience. Her diction is clear; her Italian needs work, but she is an outstanding artist.”

Mozart, Le Nozze di Figaro, Teatro Comunale di Firenze, Riccardo Muti

The Times (UK)

“Apart from her appearance in the Scottish Opera Orfeo at the end of last year, Margaret Marshall has scarcely been heard in Britain. On the evidence of her Countess in Florence that omission should be repaired immediately. Her soprano has a cool, translucent quality with an underlying melancholy which fits her ideally for the part. She delivered “Porgi amor” – an opening aria all too many sopranos use to find their way into the role, with admirably architected-phrases that are usually only heard in the recording studio.”

Studying Lieder with the best

In 1971, I was awarded a Sir James Caird Travelling Scholarship and Herbert Wiseman Prize to study abroad. I had recently graduated from the Academy (now the Royal Scottish Conservatoire) and was based in Stirling, travelling to Carlisle regularly for lessons with Ena. As you will already have picked up if you have read the other stories, as far as I was concerned Ena was the perfect teacher and so I asked, in all sincerity, if travelling to Carlisle for my lessons would count as travelling abroad!

Unsurprisingly the Trust said no, it really did mean I needed to study outside of the UK. Ena was also fully on board and reassured me that I would also continue to study with her. The head of the panel, Watson Forbes, was very keen for me to study with Hans Hotter, who as many readers of this site will know was a highly renowned German bass/baritone – indeed one of the great voices of the 20th century.

Mr Hotter was perhaps most famous for his Wagnerian roles but also an exceptional Lieder singer.

The first vision that comes to mind when I think of him was his sheer physical presence. He was a tall, imposing character with a huge voice to match. He was also an exceptionally kind man, as I would learn in the coming years.

At my audition, where I sang the Strauss lied “Allerseelen.” I remember feeling diminutive in his presence and thinking keenly how tiny my voice seemed compared with his. The audition went well, and he accepted me as a student. I had recently married and while in a parallel life I might have been settling into my new home with my husband, instead I found myself setting off for Munich where I was to stay for three months. I must add here that my husband has never been anything but fully supportive of my career. When we met I don’t think either of us imagined the direction my life would take, but he embraced it and understood that pursuing a singing career would, if I were successful, mean that I would be away from home a lot.

Munich was the start of that. I really had barely travelled abroad at this point and certainly not by myself for three months. I was horribly home-sick and ended up only managing six weeks for my first visit. Mr Hotter was incredibly supportive, never pressured me and just said I should come back when I felt ready. After that I made regular visits ever month or so, staying for a couple of weeks at a time.

The main reason Ena and Mr Forbes were keen for me to study with Hans Hotter was to extend my knowledge and understanding of Lieder singing. Mr Hotter may have had a large voice, but he also had the most amazing ability to pare down his voice to the most exquisite pianissimo. This is something I learned from him in our studies together.

We studied a lot of songs, but I particularly enjoyed the Lieder of Wolf and Richard Strauss. Mr Hotter had been a notable creator of many of Strauss’s roles for baritone and therefore could give me unique insight into the singing of Strauss’s music. I soon came to realise how fortunate I was to have not just one but two great artists as my teachers – and they complemented each other very well.

My daughter Nicola asked me if there is any benefit in studying with someone who has the same voice type, which essentially means studying with a female if you are female or a male if you are male. I would say ultimately no – what matters is that you understand the language of your teacher and that you are able to apply what they say to your voice. My voice on the surface resembled Ena’s more than Mr Hotter’s and not only for the obvious reason that I am a soprano! But I arrived in Munich with a developed technique and with Mr Hotter we were able to build on that. The top of my voice especially benefitted from our collaboration, and through the focus on pianissimo singing improved my ability to “float” my voice.

I am delighted for two reasons to be able to include these three songs (Du meines Herzens Krönelein, Ich wollt’ein Sträusslein Binden, and Schlagende Herzen) from a recital at the Wigmore Hall in 1976, on the Songbird platform. First, they are just wonderful songs both to sing and to listen to. Collectively they showcase not only the passionate, spirited and beautiful soaring phrases that characterise Strauss’s vocal music, but also his humorous side which is present here in Schlagende Herzen, and can be found in other songs including Für Fünfzehn Pfennige, Hat Gesagt bleibt’s nicht dabei, and Schlechtes Wetter, which are great fun to sing.

Second, they feature my dear friend John Fraser as accompanist. John subsequently made his name as a highly successful classical recording producer. We performed a lot together in our earlier years, after meeting at The High School in Stirling. We would enter local music competitions together, give local recitals and even, as John reminded me recently, perform at church daffodil teas. I look back on those times, starting when we were just talented teenagers exploring our love of music and performing together, with enormous affection. I am delighted that we can include a little piece of our joint music making on this platform, which would also not exist without John’s encouragement and persistence. Thank you to the BBC, and particularly Yvette Pusey, for enabling me to include it.

“Margaret Marshall, a charming soprano who comes from Stirling, and her very accomplished and sympathetic accompanist John Fraser – also from Stirling – gave members and their friends an evening to remember. This was in fact the first major recital that the two artists had given together, but their balance and oneness belied this. Perhaps the fact that they grew up together in Stirling and performed together there, was the secret of their success. Margaret Marshall gained the Sir James Caird travelling scholarship which enabled her to study under Ena Mitchell and Hans Hotter in Munich. Her voice was very well suited to the Lieder she sang – it was both powerful and controlled with a beauty of intonation.”

The beauty of English song

I sang a lot of English song at the start of my career. It is ideal for young singers as the range is not too extended and for native English speakers not yet proficient in foreign languages, there are definite advantages to singing in your own tongue, even if we do not sing in quite the same way we speak. When it comes to word painting for example – which in singing means to paint a metaphorical picture with the colour of your voice to capture the atmosphere of the words – this is certainly easier in a language you are intimate with.

Ena was a master of word painting and the English repertoire (which demands it) and was full of suggestions for works I could sing by composers including Vaughan Williams, Herbert Howells, Gustav Holst, Benjamin Britten, William Walton and Gerald Finzi.

Finzi’s “Dies Natalis” or “day of birth,” which is included in this Songbird programme, describes the wonder and greatness of the gift of life and the entrance to the world from the new born child’s experience. It is innocent, pure, direct and full of wonder. The words are exquisite, the orchestral accompaniment lush, warm and at times heart-breaking – combining to capture the wonder of birth and how we all come to live on this earth. It is a perfectly designed work of art from start to finish, with a subtle inflection of the word setting and the arching of the phrases. I find the last two movements, “How like an angel” and “These little limbs, these eyes, these hands, this panting heart” with their long melodic lines, especially moving.

It helps to love whatever music you are singing and performing, but I find this to be particularly true in the case of this piece. The subject matter is so delicate and intimate that it needs to be approached with real care, tenderness and a purity of voice that enables you to capture the innocence required.

I certainly loved it and that is why I suggested it to the conductor Gunter Kehr as a work that we could perform together. He had never heard it before and I think it was in a completely different style to anything he had played before. But he listened to it and immediately identified with the beauty of the work. I was thrilled when he said we would perform it together and his Mainzer Kammerorchester made a splendid realisation of the music.

Having obtained a copy of the recording from the Rundfunk, I was very keen to include it in this programme, not only because it was a piece I loved singing but because perhaps more than any other music, it reminds me of Ena and her extraordinary musicality and gift for word painting, which is required throughout this piece right from the first phrase and which I was so fortunate to benefit from.

However, I knew that Gunter had passed away, and I did not have any contact with the orchestra. I took the obvious route and looked them up on the internet, found a telephone number and called it. Incredibly the woman that answered the phone happened to be his widow who somehow after all these years recognised my speaking voice. She was very happy to agree to my request and put me in touch with the manager of the orchestra, who also agreed, as did Boosey and Hawkes.

Coincidentally I learned 2020 also marks 120 years since Finzi was born. Against the backdrop of other events being planned to mark this date, I am delighted to make a small contribution to his memory with this recording.

“Margaret Marshall gained the Sir James Caird travelling scholarship which enabled her to study under Ena Mitchell and Hans Hotter. Her voice was very well suited to the first part of the programme – it was both powerful and controlled, with a beauty of intonation. Her dramatic interpretations of Wolf and “The Three Songs” by William Walton were a sheer delight. Her versatility was displayed b y the contemporary English songs which she sang in the second half of the programme.”